PLC Chapter VI – Control Structures Statement

A control structure is a control statement and the collection of statements whose execution it controls.

A program is usually not limited to a linear sequence of instructions. During its process, it may bifurcate, repeat code or take decisions. For that purpose, C++ provides control structures that serve to specify what has to be done by our program, when and under which circumstances.

With the introduction of control structures we are going to have to introduce a new concept: the compound-statement or block. A block is a group of statements which are separated by semicolons (;) like all C++ statements, but grouped together in a block enclosed in braces “{ }”

{ statement1; statement2; statement3; }

Most of the control structures require a generic statement as part of its syntax. A statement can be either a simple statement which is a simple instruction ending with a semicolon or a compound statement which is several instructions grouped in a block, like the one just described. In the case that a simple statement, it does not need to enclose it in braces ({}). But in the case of a compound statements , it must be enclosed between braces ({}), forming a block.

A. Selection Structure

- Two-Way Selection Statements

The if keyword is used to execute a statement or block only if a condition is fulfilled. Its form is:

if (condition) statement

Where condition is the expression that is being evaluated. If this condition is true, statement is executed. If it is false, statement is ignored (not executed) and the program continues right after this conditional structure.

For example, the following code fragment prints x is 100 only if the value stored in the x variable is indeed 100:

|

if (x == 100) cout << “x is 100”; |

If we want more than a single statement to be executed in case that the condition is true we can specify a block using braces { }:

|

if (x == 100) { cout << “x is “; cout << x; } |

We can additionally specify what we want to happen if the condition is not fulfilled by using the keyword else. Its form used in conjunction with if is:

if (condition) statement1 else statement2

For example:

|

if (x == 100) cout << “x is 100”; else cout << “x is not 100”; |

prints on the screen x is 100 if indeed x has a value of 100, but if it has not -and only if not- it prints out x is not 100.

The if + else structures can be concatenated with the intention of verifying a range of values. The following example shows its use telling if the value currently stored in x is positive, negative or none of them (i.e. zero):

|

if (x > 0) cout << “x is positive”; else if (x < 0) cout << “x is negative”; else cout << “x is 0”; |

Remember that in case that we want more than a single statement to be executed, we must group them in a block by enclosing them in braces { }.

- Nesting Selection Statements

if( boolean_expression 1) {

// Executes when the boolean expression 1 is true

if(boolean_expression 2) {

// Executes when the boolean expression 2 is true

}

}

Nested if-else statements mean that you can use one if or else if statement inside another if or else if statements.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main () {

// local variable declaration:

int a = 100;

int b = 200;

// check the boolean condition

if( a == 100 ) {

// if condition is true then check the following

if( b == 200 ) {

// if condition is true then print the following

cout << “Value of a is 100 and b is 200” << endl;

}

}

cout << “Exact value of a is : ” << a << endl;

cout << “Exact value of b is : ” << b << endl;

return 0;

}

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces the following result:

Value of a is 100 and b is 200

Exact value of a is : 100

Exact value of b is : 200

- Multiple-Way Selection Statements

Multiple-Way Selection Statements objective is to check several possible constant values for an expression. Something similar to what we did at the beginning of this section with the concatenation of several if and else if instructions. Its form is the following:

switch (expression)

{

case constant1:

group of statements 1;

break;

case constant2:

group of statements 2;

break;

default:

default group of statements

}

It works in the following way: switch evaluates expression and checks if it is equivalent to constant1, if it is, it executes group of statements 1 until it finds the break statement. When it finds this break statement the program jumps to the end of the switch selective structure.

If expression was not equal to constant1 it will be checked against constant2. If it is equal to this, it will execute group of statements 2 until a break keyword is found, and then will jump to the end of the switch selective structure.

Finally, if the value of expression did not match any of the previously specified constants (you can include as many case labels as values you want to check), the program will execute the statements included after the default: label, if it exists (since it is optional).

Both of the following code fragments have the same behavior:

| switch example | if-else equivalent |

| switch (x) {

case 1: cout << “x is 1”; break; case 2: cout << “x is 2”; break; default: cout << “value of x unknown”; } |

if (x == 1) {

cout << “x is 1”; } else if (x == 2) { cout << “x is 2”; } else { cout << “value of x unknown”; } |

The switch statement is a bit peculiar within the C++ language because it uses labels instead of blocks. This forces us to put break statements after the group of statements that we want to be executed for a specific condition. Otherwise the remainder statements -including those corresponding to other labels- will also be executed until the end of the switchselective block or a break statement is reached.

For example, if we did not include a break statement after the first group for case one, the program will not automatically jump to the end of the switch selective block and it would continue executing the rest of statements until it reaches either a break instruction or the end of the switch selective block. This makes it unnecessary to include braces { }surrounding the statements for each of the cases, and it can also be useful to execute the same block of instructions for different possible values for the expression being evaluated. For example:

|

Notice that switch can only be used to compare an expression against constants. Therefore we cannot put variables as labels (for example case n: where n is a variable) or ranges (case (1..3):) because they are not valid C++ constants.

If you need to check ranges or values that are not constants, use a concatenation of if and else if statements.

B. Iteration Statements

An iterative statement is one that causes a statement or collection of statements to be executed zero, one, or more times. An iterative statement is often called a loop. Iteration is the very essence of the power of the computer. If some means of repetitive execution of a statement or collection of statements were not possible, programmers would be required to state every action in sequence; useful programs would be huge and inflexible and take unacceptably large amounts of time to write and mammoth amounts of memory to store.

- Counter-Controlled Loops

A counting iterative control statement has a variable, called the loop variable, in which the count value is maintained. It also includes some means of specifying the initial and terminal values of the loop variable, and the difference between sequential loop variable values, often called the stepsize. The initial, terminal, and stepsize specifications of a loop are called the loop parameters.

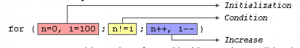

Its format is: for (initialization; condition; increase) statement;

and its main function is to repeat statement while condition remains true, like the while loop. But in addition, the for loop provides specific locations to contain an initialization statement and an increase statement. So this loop is specially designed to perform a repetitive action with a counter which is initialized and increased on each iteration.

It works in the following way:

- initialization is executed. Generally, it is an initial value setting for a counter variable. This is executed only once.

- condition is checked. If it is true the loop continues, otherwise the loop ends and statement is skipped (not executed).

- statement is executed. As usual, it can be either a single statement or a block enclosed in braces { }.

- finally, whatever is specified in the increase field is executed and the loop gets back to step 2.

Here is an example of countdown using a for loop:

| // countdown using a for loop

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { for (int n=10; n>0; n–) { cout << n << “, “; } cout << “FIRE!\n”; return 0; } |

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, FIRE! |

The initialization and increase fields are optional. They can remain empty, but in all cases the semicolon signs between them must be written. For example we could write: for (;n<10;) if we wanted to specify no initialization and no increase; or for (;n<10;n++) if we wanted to include an increase field but no initialization (maybe because the variable was already initialized before).

Optionally, using the comma operator (,) we can specify more than one expression in any of the fields included in a forloop, like in initialization, for example. The comma operator (,) is an expression separator, it serves to separate more than one expression where only one is generally expected. For example, suppose that we wanted to initialize more than one variable in our loop:

|

This loop will execute for 50 times if neither n or i are modified within the loop

n starts with a value of 0, and i with 100, the condition is n! = i (that n is not equal to i). Because n is increased by one and i decreased by one, the loop’s condition will become false after the 50th loop, when both n and i will be equal to 50.

- Logically Controlled Loops

Logically controlled loops are more general than counter-controlled loops. Every counting loop can be built with a logical loop, but the reverse is not true. Also, recall that only selection and logical loops are essential to express the control structure of any flowchart.

Pre-test Loop

In the pretest version of a logical loop (while), the statement or statement segment is executed as long as the expression evaluates to true.

Its format is: while (expression) statement

and its functionality is simply to repeat statement while the condition set in expression is true.

For example, we are going to make a program to countdown using a while-loop:

| // custom countdown using while

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { int n; cout << “Enter the starting number > “; cin >> n;

while (n>0) { cout << n << “, “; –n; } cout << “FIRE!\n”; return 0; } |

Enter the starting number > 8

8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, FIRE! |

When the program starts the user is prompted to insert a starting number for the countdown. Then the while loop begins, if the value entered by the user fulfills the condition n>0 (that n is greater than zero) the block that follows the condition will be executed and repeated while the condition (n>0) remains being true.

The whole process of the previous program can be interpreted according to the following script (beginning in main):

- User assigns a value to n

- The while condition is checked (n>0). At this point there are two possibilities:

* condition is true: statement is executed (to step 3)

* condition is false: ignore statement and continue after it (to step 5) - Execute statement:

cout << n << “, “;

–n;

(prints the value of n on the screen and decreases n by 1) - End of block. Return automatically to step 2

- Continue the program right after the block: print FIRE! and end program.

When creating a while-loop, we must always consider that it has to end at some point, therefore we must provide within the block some method to force the condition to become false at some point, otherwise the loop will continue looping forever. In this case we have included –n; that decreases the value of the variable that is being evaluated in the condition (n) by one – this will eventually make the condition (n>0) to become false after a certain number of loop iterations: to be more specific, when n becomes 0, that is where our while-loop and our countdown end.

Of course this is such a simple action for our computer that the whole countdown is performed instantly without any practical delay between numbers.

Post-Test Loop

In the posttest loop (do), the loop body is executed until the expression evaluates to false. The only real difference between the do and the while is that the do always causes the loop body to be executed at least once.

Its format is: do statement while (condition);

Its functionality is exactly the same as the while loop, except that condition in the do-while loop is evaluated after the execution of statement instead of before, granting at least one execution of statement even if condition is never fulfilled. For example, the following example program echoes any number you enter until you enter 0.

| // number echoer

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { unsigned long n; do { cout << “Enter number (0 to end): “; cin >> n; cout << “You entered: ” << n << “\n”; } while (n != 0); return 0; } } |

Enter number (0 to end): 12345

You entered: 12345 Enter number (0 to end): 160277 You entered: 160277 Enter number (0 to end): 0 You entered: 0 |

The do-while loop is usually used when the condition that has to determine the end of the loop is determined within the loop statement itself, like in the previous case, where the user input within the block is what is used to determine if the loop has to end. In fact, if you never enter the value 0 in the previous example you can be prompted for more numbers forever.

- User-Located Loop Control Mechanisms

The break statement

Using break we can leave a loop even if the condition for its end is not fulfilled. It can be used to end an infinite loop, or to force it to end before its natural end. For example, we are going to stop the count down before its natural end (maybe because of an engine check failure?):

| // break loop example

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { int n; for (n=10; n>0; n–) { cout << n << “, “; if (n==3) { cout << “countdown aborted!”; break; } } return 0; } |

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, countdown aborted! |

The continue statement

The continue statement causes the program to skip the rest of the loop in the current iteration as if the end of the statement block had been reached, causing it to jump to the start of the following iteration. For example, we are going to skip the number 5 in our countdown:

| // continue loop example

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { for (int n=10; n>0; n–) { if (n==5) continue; cout << n << “, “; } cout << “FIRE!\n”; return 0; } |

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 4, 3, 2, 1, FIRE! |

The go to statement

goto allows to make an absolute jump to another point in the program. You should use this feature with caution since its execution causes an unconditional jump ignoring any type of nesting limitations.

The destination point is identified by a label, which is then used as an argument for the goto statement. A label is made of a valid identifier followed by a colon (:).

Generally speaking, this instruction has no concrete use in structured or object oriented programming aside from those that low-level programming fans may find for it.

For example, here is our countdown loop using goto:

| // goto loop example

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main () { int n=10; loop: cout << n << “, “; n–; if (n>0) goto loop; cout << “FIRE!\n”; return 0; } |

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, FIRE! |

The exit function

exit is a function defined in the cstdlib library. The purpose of exit is to terminate the current program with a specific exit code. Its prototype is:

| void exit (int exitcode); |

The exitcode is used by some operating systems and may be used by calling programs. By convention, an exit code of 0means that the program finished normally and any other value means that some error or unexpected results happened.

- Iteration Based on Data Structure

A general data-based iteration statement uses a user-defined data structure and a user-defined function (the iterator) to go through the structure’s elements. The iterator is called at the beginning of each iteration, and each time it is called, the iterator returns an element from a particular data structure in some specific order. For example, suppose a program has a user-defined binary tree of data nodes, and the data in each node must be processed in some particular order. A user-defined iteration statement for the tree would successively set the loop variable to point to the nodes in the tree, one for each iteration. The initial execution of the user-defined iteration statement needs to issue a special call to the iterator to get the first tree element. The iterator must always remember which node it presented last so that it visits all nodes without visiting any node more than once. So, an iterator must be history sensitive. A user-defined iteration statement terminates when the iterator fails to find more elements.